SOURCE: Smithsonian Magazine

DATE: May 30, 2019

SNIP: Alaska in March is supposed to be cold. Along the north and west coasts, the ocean should be frozen farther than the eye can see. In the state’s interior, rivers should be locked in ice so thick that they double as roads for snowmobiles and trucks. And where I live, near Anchorage in south-central Alaska, the snowpack should be deep enough to support skiing for weeks to come. But this year, a record-breaking heatwave upended norms and had us basking in comfortable—but often unsettling—warmth.

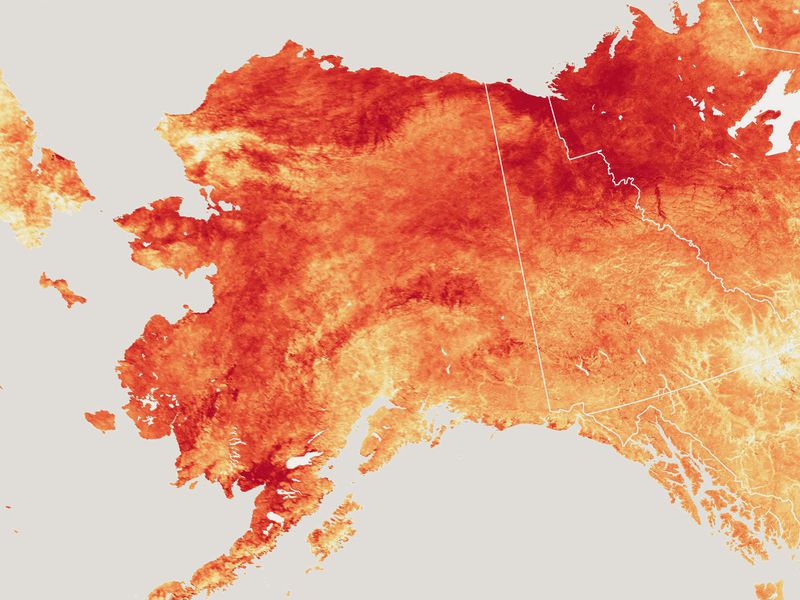

Across Alaska, March temperatures averaged 11 degrees Celsius above normal. The deviation was most extreme in the Arctic where, on March 30, thermometers rose almost 22 degrees Celsius above normal—to 3 degrees. That still sounds cold, but it was comparatively hot.

The state’s wave of warmth was part of a weeks-long weather pattern that shattered temperature records across our immense state, contributing to losses of both property and life.

On April 15, three people, including an 11-year-old girl, died after their snowmobiles plunged through thin ice on the Noatak River in far northwestern Alaska. Earlier in the winter, 700 kilometers south, on the lower Kuskokwim River, at least five people perished in separate incidents when their snowmobiles or four-wheelers broke through thin ice. There were close calls too, including the rescue of three miners who spent hours hopping between disintegrating ice floes in the Bering Sea near Nome. Farther south, people skating on the popular Portage Lake near Anchorage also fell through thin ice. Varying factors contributed to these and other mishaps, but abnormally thin ice was a common denominator.

The steady decline of sea ice is old news, but 2019 brought exceptional conditions. In January, a series of warm storms began breaking apart the ice, which had formed late and was thinner than usual. By late March, the Bering Sea was largely open, at a time when the ice usually reaches its maximum for the year, which historically has been as much as 900,000 square kilometers (more than twice the size of the province of Alberta). In April, U.S. federal scientists reported coverage was even lower than the unprecedented low extent of 2018. By mid-May, ice that should have persisted into June was almost entirely gone.

Beyond the immediate impacts on people and infrastructure, less ice in the Bering and in the neighboring Chukchi Sea to the north have far-reaching atmospheric effects in Alaska. As Thoman explains, the massive area of newly open water creates warmer air temperatures and provides more moisture to storms. It can increase coastal erosion and winter rain or even produce heavier snow far inland. Researchers are also investigating whether disappearing sea ice is affecting continental weather patterns.